Graffiti

By Johanna Michelle Lim

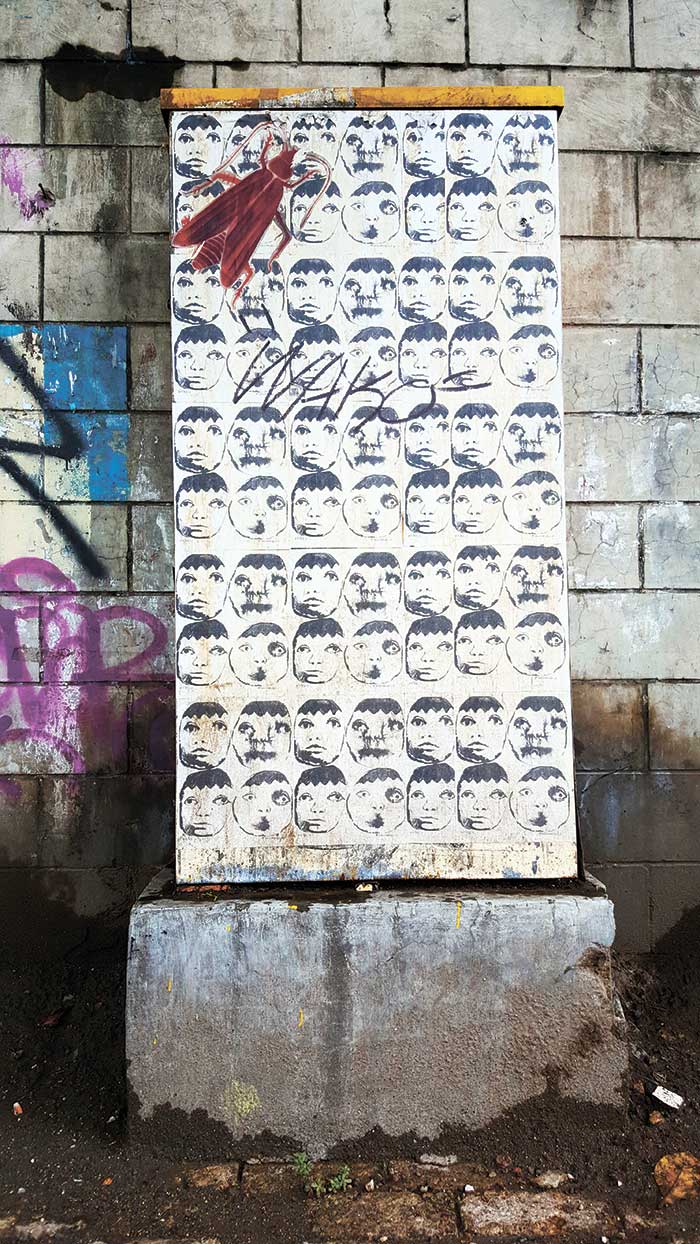

Images: Freon L. Ollival

THOSE of us who brave the streets constantly find layers and leavings of someone else’s life; spit and phlegm stuck to the soles of shoes, signage after signage of politicos and masseuses, footsteps and handprints, dirt and debris, to create the archetype of the metropolis as we know it: a city in a state of hysteria so constant that it almost goes unnoticed.

Once in a while, when tuned in to the rhythms of its restlessness, you start to question, Wasn’t there something here before? Spaces once occupied are now blank surfaces, or the other way around. Something has changed but you can’t quite trace the trajectory of its befores and afters.

Perhaps it’s the invasion of what is seemingly personal, the loss of entitlement to what is and isn’t yours, that fascinates and brings us back to the streets time and time again. There’s the liberation of knowing space is not anyone’s, but everyone’s. And along with it, the jarring frustration that it isn’t anyone’s, purely yours especially, but everyone’s.

These two, space and ownership, are central to those who choose the streets as their medium, so much so that even if street art has outlived its detritus as an instrument for propaganda (and consequently the need for artists to remain anonymous), it still retains the feel of a deliberate rebellion. Graffiti, in its heart, gives in to the sinful, socially equalizing but questionable, appeal of calling something mine.

Staking claims to public spaces – walls, jeepneys, lampposts, fences – is not dissimilar to staking claims to someone else, really. Mine, mine, mine. You clasp their hand in an attempt to keep and defend. Ownership, however illusory, is addicting. And yet its mass appeal often strikes the chord of almost everyone who have at one time inwardly shouted, “Screw the world. Screw humanity.”

Never mind if we can’t completely grasp the social commentaries parlayed to reduced visual elements. All we know is that We are Children of the Wild, Karingkay and HardChick Were Here, and We Must Resist. The lines take on a certain poetic romanticism especially when, like poetry, they are never truly grasped no matter how many times you pass by them. On a sunny day in July last year, I found myself, along with several others who chucked their footwear and sat down on the grass of I.T. Park, watching the artists of the UBEC Crew – Soika, Uzi, Bart Bombs, Kidlat – amongst them working on a 12 x 12 foot canvass that seemed to mutate on its own every time you looked at it.

With several figures working on an area so finite, there’s no other way to assert identity but to replace one artwork for another. After several minutes, a psychedelic pattern would be replaced by a coffee cup, which would then be later replaced by a clownlike smile. This happened several times over in a course of one afternoon, a total of almost ten finished artworks in a single canvass which had to be covered, layered, archived, to never to be seen again.

And yet, after the box of spray cans have been consumed and the brushes dried, none of them seemed to express any resentment to what has been lost.

The nature of street art is to accept the ephemeral. And if the elusive Banksy’s dictum, ironically juxtaposed beside a photo of lovebirds, is to be believed, “As soon as you meet someone, you know the reason you will leave them.” We toss the layers and leavings of our own lives for someone else to find.