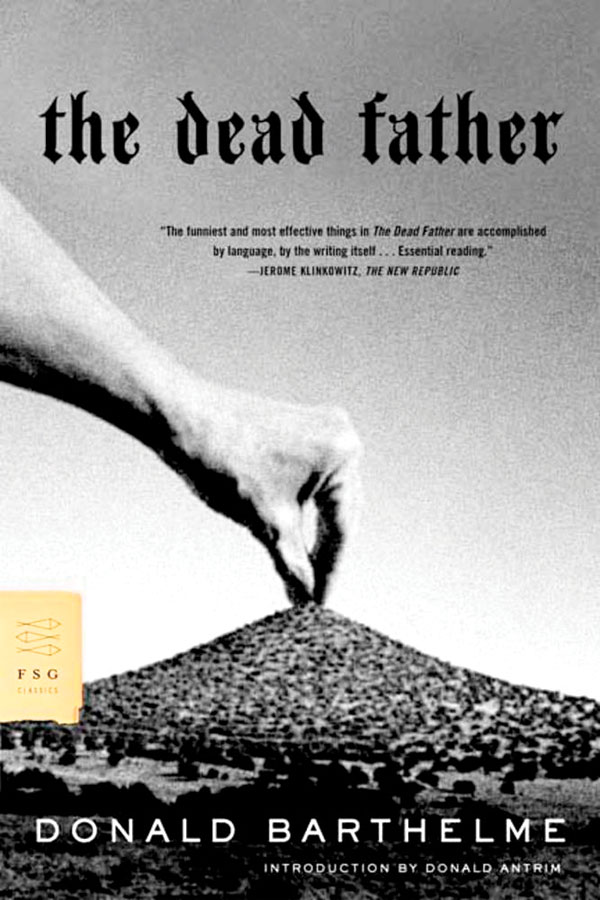

Donald Barthelme’s ‘The Dead Father’

I SAT and read The Dead Father, a formative work of postmodernist fiction, in three bursts: afternoon, evening, then morning. Finishing the novel left me with cerebral indigestion: I am still deciphering the points of the story (despite knowing it’s meant to be essentially and playfully absurd and ironic — to quote, “To find a lost father: the first problem in finding a lost father is to lose him” — which, I suppose, are postmodern devices, gimmicks, and tricks); and I am still weighing its strengths and — for my lack of vocabulary, I shall call them — “flaws,” which mirror my own flaws, for I, the reader, unavoidably give birth to the text, changing it and constructing meaning from it according to myself — my capacity, standard, and perspective. Postmodernism is a literary genre that is self-conscious of the reader’s authority over the text.

Resembling a Kafkaesque world with a dystopian backdrop, the story was about a surrealistic funeral march (only revealed at the novel’s end) for the Dead Father who believed that his children were bringing him into the “Golden Fleece,” where he would recover not just his life and dominion over the world but also his youth. The Dead Father was a 3,200-cubit quasi-omnipotent — yet vain, temperamental, lascivious, and tyrannical — giant who was “dead, but still with [them], still with [them], but dead.” A crew of nineteen men hauled him by means of a cable wire across strange territories to bury him into his equally gigantic grave.

Resembling a Kafkaesque world with a dystopian backdrop, the story was about a surrealistic funeral march (only revealed at the novel’s end) for the Dead Father who believed that his children were bringing him into the “Golden Fleece,” where he would recover not just his life and dominion over the world but also his youth. The Dead Father was a 3,200-cubit quasi-omnipotent — yet vain, temperamental, lascivious, and tyrannical — giant who was “dead, but still with [them], still with [them], but dead.” A crew of nineteen men hauled him by means of a cable wire across strange territories to bury him into his equally gigantic grave.

Barthelme’s narrative on The Dead Father was a “fragmented verbal collage”; the sentences were deconstructed —

The wall trembling. The alcove shaped like an egg. Quilt slipping toward the edge. The mountain. A set of stone steps. The cathedral. Bronze doors intricately worked with scenes. Row of grenadiers in shakos. Kneeling. Interior of the egg.

— and some dialogues were written with the shock of non-sequitor (random and unrelated responses to “generate new meanings”), as though in a Freudian free-association game. Take this voice-over of a conversation between two female characters in the book for example:

Thought I heard a dog barking.

It’s possible. The simplest basic units develop into the richest natural patterns.

Are you into spanking?

No, I’m not.

Pity. We could have something going.

I’m not into that.

Where can a body get hit around here?

Pop one of these if you’d like a little lift.

Barthelme’s daring, unorthodox, even “alien” use of language (a signature Beckettian wordplay, I say, as one cannot not think of Samuel Beckett while reading The Dead Father), his off-the-nuts hilarity, and his ingenious book-within-a-book, A Manual for Sons — which contained the groundwork themes from which the novel stood out, such as fatherhood and its eternal influence on all the father’s procreations, and the sons’ unconscious desires of patricide — were the novel’s strongest suits. From A Manual for Sons.

Then they attacked [the father] with sumo wrestlers, giant fat men in loincloths. We countered with loincloth snatchers… We were successful. The hundred naked fat men fled… When you have rescued the father from whatever terrible threat menaces him, then you feel, for a moment, that you are the father and he is not. For a moment. This is only the moment in your life you will feel this way.

Doubtlessly I enjoyed this challenging book, but it left me unhappy, with a bad aftertaste, like a terrible hangover from a “trip.” I awaited for the “aesthetic event” — my merit of all the books I have read — to happen, but it did not occur throughout the read; perhaps I glimpsed a few flashes of it, but they were nonetheless dim even in that respect.

The ending, which I found human and sentimental, did not find its mark in me. It’s a rigorous task for me to rate this book objectively since I am still naive to the avant-garde and postmodern traditions of literature. But conclusively, the late and influential Barthelme was a genius left in his postmodern school and playground, experimenting with possible forms of fiction, leading an evolution that changes the way we think about the written word.