Finally hearing the birds sing

By Shane Carreon

IN the middle of the crowd and all the glazed donuts that Sunday, a poem hit me on the forehead as in the gut. There I was, supposedly Bisdak, reading Michael Obenieta’s poem “Kay ang kahilom usa sab ka siloy” in its English translation because I couldn’t understand it in its original Cebuano.

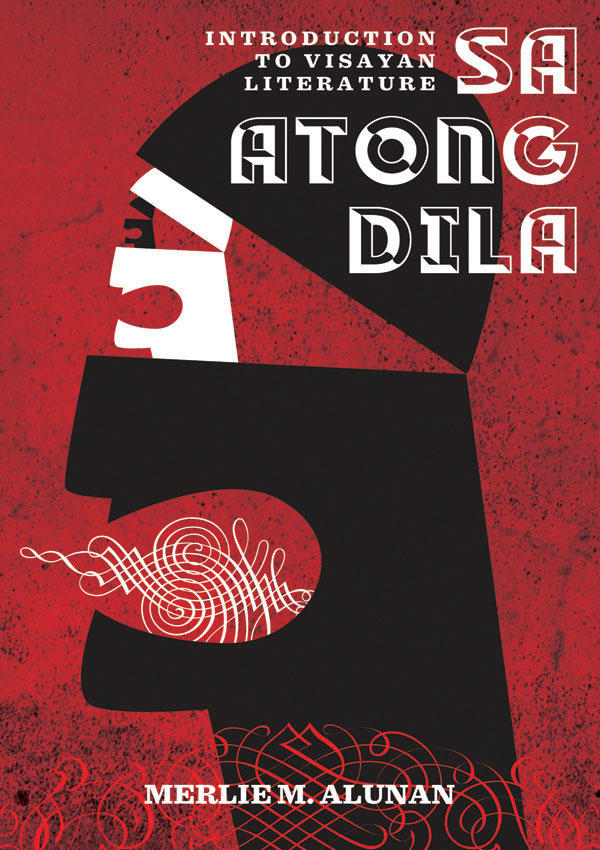

Earlier that day I bought Merlie Alunan’s book, “Sa Atong Dila,” with a nearly uncontainable excitement: the book is a first-of-its-kind collection of literature from all over the Visayas. What with the hype about mother tongue being (finally!) taught in our classrooms, I thought the book — the most comprehensive anthology, by far, of Visayan literature from east to west, from tikang ha mga kasanhi to binag-ong mga balak to sugidanon to panaysayon — was a library must-have, a teacher must-have, even. At the festival where I got it, copies sold out nearly before they even reached the table. So I thought word about the book had spread like wildfire, only to find out that most of the buyers were fellow writers themselves attending the festival; the few school teachers I knew who were teaching the Mother Tongue haven’t even heard about it. Oh, there can be very long conversations about concerns with book publishing and marketing in the country, how the machinery of Wattpad stories seems to have overrun Philippine Literature, how rare it is to find books in our mother tongues, whether in commercial bookstores or in school and government libraries. I often find myself asking why there’s a lack of interest in literature in our own mother tongue, in general, and the book “Sa Atong Dila,” in particular?

A long march through labyrinthine socio-cultural explanations might be an answer I’d rather not begin with, now having found myself in a familiar ending: the reality of a supposedly Bisdak having donuts and coffee in Cebu while reading the English translation of a Cebuano poem.

Some miseducation has come to be quite successful. The beginnings of my own reading life, for example, followed a parade of books readily available to be either borrowed from libraries or bought from bookstores in the city; this meant Dr. Seuss, the Wakefields, The Little Prince. At that time literature, that mirror-world in beautiful language, was — and it seemed, could only be — in English, a given reinforced without malice and with all good, albeit blind, intentions by family and school community. There was little to no talk of Visayan literature, at least not in the house, neighborhood and schools where I was growing up; possibly the closest were the overheard bits of dialogue from AM radio drama the help listened to during mid-afternoons when I was cooped indoors, resisting forced siesta. What was difficult then was not only finding Visayan literature, but also discovering where to access it, the secret door leading outdoors.

Which makes me think nowadays are better. There are more doors, which aren’t much of a secret anymore. There is the growing number of artists who are using Bisaya in films, songs, stories, and performance poetry, among others. Not too long ago, “Paranormal Romance” filled theatres; these days, “Labyu Langga” is played in radio stations, hit by the thousands in Youtube, included in a movie soundtrack. More are recognising our mother tongue as meaningful beyond marketplace and jeepney exchanges, as a way of keeping alive the beautiful in our way of life and living as a people and culture.

Doors, too, are the recent mother tongue policy implemented in our grade schools. And the teachers, their paradigms have shifted, having realized the urgent importance to introduce Visayan literature to older students.

These teachers are often peculiarly called by our current academic system as English teachers, tasked to teach Philippine literature — too often in English — to grow within students pride for one’s cultural identity. Some of them, graduate students at the University of the Philippines Cebu, whom I had a chance to meet, asked me for a list. A list of writers’ names, a list of mother tongue literature, a list of places where to find them. Where the door leading outdoors is.

I could only give them all the little I had at the time, myself not too far ahead of them in the search. There was the university library Cebuano Studies Center, the website balaybalakasoy, the books by various singular authors that were spread anywhere but the popular and accessible bookstores, and the irregular late night balak readings in the city. I remember seeing resigned faces and thinking how it was so much easier to get an anthology of American literature.

This was, of course, some time before Alunan’s “Sa Atong Dila: Introduction to Visayan Literature,” which is the widest door leading outdoors that I have yet gone through. An anthology of poetry, fiction, drama, and essays in the mother tongues of Eastern, Central, and Western Visayas, in a breadth that spans folk till contemporary times. A seemingly endless list of writers’ names and mother tongue literature, all in one book. Also, guide questions like door knobs to open the door wider.

And English translations, too, for the lost who have found their way and are welcomed home.